[written Fall of 2007]

Whatever so disposes the human Body that it can be affected in a great many ways, or renders it capable of affecting external Bodies in a great many ways, is useful to man;

-Spinoza, Ethics, Part IV, Proposition 38

This paper is going to be a bit of an experiment in description, as it borrows from the two poles of philosophical pursuit that have over the last century been reported to have grown apart, the Continental and the Analytic. Yet now the rumor is that they are coming together, again (α). So this paper starts where much leaves off, in between.

The under comparison is that of transgender and its successive, trans-sexuality. Much plagues those who take such a diverse category for their subject, attempting to gather so many in one conceptual net and to call them by one name; and then to pick each out by kind, as if we might through measurement and definition find a genealogy of desires and practices, a phylum, a taxonomy, and eventually an etiology which organize these behaviors so as to make them meaningful to ourselves and others. That is not the aim here. What is to be discovered, if anything, is how trans-practices manifest by their very nature across phyla, no matter their destination, but also how in doing so, they enrichly form new bodies, and new capacities for wholeness.

The starting point is the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari, difficult thinkers to begin with because so much of what they write, even, or especially as they endeavor to be analytical, is defiant of our usual categories of intellectual organization. Hierarchies, categories, binaries, universals, systems, and tree-branching structures of thought are not spared. Or rather they are spared, but de-centralized, as they propose alternative ana-lysis to the way the world manifests itself. Yet undeterred we shall begin by plucking from them a single metaphor, an analogy, a homology, a model which is none of these things and possibly more (a map), and use it to unfold what may be happening when a person of one supposed gender begins his or her journey towards another.

We, following Deleuze and Guattari, take from biology as a starting point the remarkable phenomena widely called “sexual deception” or more pointedly, and technically: the conditions, structures and events surrounding “pseudocopulation” wherein an orchid sexually masquerades as a wasp. As biologist Manfred Ayasse describes,

Ophys flowers mimic virgin females of their pollinators, and male insects are lured to the orchid by volatile semiochemicals and visual cues. At close range, chemical signals from the flowers elicit sexual behavior in males, which try to copulate with the flower labellum and respond as if in the presence of female sex pheromones. Thereby the male touches the gynostemium, and the pollinia may become attached to his head or, in some species, to the tip of his abdomen. His copulatory attempts with another flower ensure that the pollinia are transferred to the flower’s stigmatic surface and pollination is ensured (Ayasse, 517)

In short, orchids particularly of the genus Chiloglottis, have evolved with the capacity to produce the sexual pheromones of a wasp that serves as its pollinator, Neozeleboria, and to visually present the appearance of the female wasp herself. What is advantageous about this example is this: just as scientists struggle to describe such imitation in a language of pure instrumentality, of surfaces, structures and behaviors, and are forced to slip into a language of intents, deceptions, lures, and rewards to make their description full, conversely, as we approach the wants and desires of trans-persons we might go beyond simply their volitions and aims, and see that even in examples of “copying” or “imitating” something more is going on, something bio-morphic. For while as striking as it may seem to a normative some that a biologically sexed woman may try in every regard within her means to become understood to be a man, that is, to be something that is not within her supposed historical capacity to be, it is perhaps even more revealing when we realize that an orchid can become indistinguishable by scent or sight from the sexual partner of a wasp (Wong, 1530). In fact, what Deleuze and Guattari want us to see is the insufficiency of a language of physical boundaries and a language of psychological aims when describing the powers of transformation, in particular, when mimicry or copying is involved. For what ultimately is in play when copies are read as authentic or inauthentic is the Platonic distinction between the good copy and the poor or deceptive imitation. In the stead of this, Deleuze and Guattari would like to use a conception of copy in which the copy is only as good as what it can do (β) , no longer being a “copy” (neither good nor bad), but an experimentation, making of both the orchid and the trans-sexual in kind, neither a deception, nor an approximation, but a real becoming, that is, a continual process a material assemblage.

Deleuze and Guattari imagine there to be a wasp-orchid assemblage, where the boundaries of the one cannot be thoroughly distinguished from the boundaries of the other. Rather it is in terms of code and traces that the stratum of a plant line intersects unexpectedly (there is nothing in the nature of a plant that would anticipate it becoming-animal in code), with the stratum of an animal line, where each becomes the function of the other. Using a vocabulary of “territory” to note the closed and open statuses of a body, as it pertains to function, Deleuze and Guattari offer a description of the wasp-orchid relation which exceeds the explanatory power of representational thinking:

The orchid deterritorializes (γ) by forming an image, a tracing of a wasp; but the wasp reterritorializes on that image. The wasp is nevertheless deterritorialized, becoming a piece in the orchid’s reproductive apparatus. But it reterritorializes the orchid by transporting its pollen. Wasp and orchid, as heterogeneous elements, form a rhizome. It could be said that the orchid imitates the wasp, reproducing the image in a signifying fashion (mimesis, mimicry, lure, etc.). But this is true only on the level of the strata — a parallelism between two strata such that a plant organization on one imitates an animal organization on the other. At the same time, something else entirely is going on: not imitation at all but a capture of code, surplus value of code, an increase in valence, a veritable becoming, a becoming-wasp of the orchid and a becoming-orchid of the wasp. (10).

It is through this notion of desire working as a rhizome between strata—the unseen way that grass grows, branching out nodulely, diversely, without center, in contrast to the sciencific analogy of the tree—that they seek to uncover the very real trans-phyla communications and creations that lie not below, nor prior to, but adjacent to the hierarchies and arboreal structures of our more common molar descriptions of life and thought (Pearson, 153),. As Pearson describes the rhizome,

A rhizome is…a subterranean ‘network of multiple branching roots and shoots, with no central axis, with no unified point of origin, and no given direction of growth’. In effect the rhizome constitutes the surplus value of evolution, always coming into being without origin, and only conceivable when evolution is understood as functioning transversally, that is, as cutting across distinct lineages (157)

it is through the rhizome that the orchid reaches the wasp, and the wasp the orchid. And as it may be suggested, how the trans reaches the pronoun, and the pronoun the trans, through others. Despite the experiences of approximation and representation that occupy many trans-individual efforts, such a rhizomic approach allows that something more significant than “copying” poorly or perfectly may be involved in trans-becomings, something productive.

In order to understand Deleuze and Guattari’s approach which includes codes, intensities and traces, we need to address their idea of the “body without organs” (BwO). The term, taken from the end of schizophrenic poet, Antoine Artaud’s radio play, “To Have Done with the Judgment of God” (δ) , is a concept designed to describe the intensive nature of a body as it is both experienced and expressed in a specific yet unhierarchized form. It is in direct contrast to a supposed body-with-organs that is by society organ-ized, furnished with organs, to particular purposes and functions. Deleuze and Guattari see in the BwO the capacities of the body to become traversed with intensities and thus possibilities that cannot be contained within its heretofore organized history, or one could say, its phylum, or kind. It is the way that the BwO unhinges analysis of events of imitation and approximation, freeing descriptions from an etiology of specific psychic aims, wants or desires (to be more like “daddy,” or to attract “men”), that it brings its greatest fecundity. As imitative pursuits show themselves to be something more than simply making copies of copies, they begin to manifest a productive desire. But how is a body without organs, found, located or recognized?

Deleuze and Guattari want us to see a priority of affects, the way that our affects actually work to define what we are capable of doing, and thus what we are. In a telling, counter-intuitive example they suggest for instance that a racehorse has less in common with a workhorse than does an ox. Working within a cartographic measure of parts which undermines any descriptive speciation, they write:

Lattitude is made up of intensive parts falling under a capacity, and a longitude of extensive parts falling under a relation. In the same way that we avoid defining a body by its organs and functions, we will avoid defining it by Species or Genus characteristics; instead we will count its affects…A race horse is more different from a workhorse than a workhorse is from an ox (257).

For, the body of a racehorse goes beyond our classifications of kinds—though these too demarcate the kinds of experiences a racehorse can have, for instance the experience of mating with a workhorse. A racehorse will likely experience things in a manner no workhorse will come to, while the ox and workhorse will have a community of affects historically determined across species. The body without organs is this veritable capacity to be defined through intensities experienced in particular ways; and from these intensities be able to disorganize from one’s history (deterritorialize), and reorganize in a line of flight, “jumping the tracks” of code so to speak, into new possibilities of material assemblage (reterritorializing), just as the orchid becomes an orchid-wasp.

How this reflects upon trans-identities is of great interest, for much of what garners the attention of scientists, advocates and trans-persons themselves is the very seemingly imitative nature of their self-projects. How would such projects be seen if taken out of the representational milieu, and into the constructive arena of body without organs transformation? What would the trans-experience look like under such a view? Deleuze and Guattari provide us a key in their explanation of how one might go about actually making (and not just finding) a body without organs. They take up again an example of apparent imitation. This time instead of a flower becoming an insect, it is a masochist’s fantasy aim of becoming a horse: bridle and all. They want to question the Freudian-lead psychological framework of causes, wants and desires that tries to make heads or tails of why a masochist may want to “be a horse” (258), and instead picture the masochist’s project as one of establishing a program of thresholds and affect transformations (ε). After a series of ritualized conditionings where the part of the horse is organized upon the body of the masochist, the question of what is happening is opened up:

What is this masochist doing? He seems to be imitating a horse, Equus eroticus, but that’s not it. Nor are the horse and the master-trainer or mistress images of the mother or father. Something entirely different is going on: a becoming-animal essential to masochism. It is a question of forces. The masochist presents it this way: Training axiom—destroy the instinctive forces in order to replace them with transmitted forces. In fact, it is less a destruction than an exchange and circulation (“what happens to a horse can also happen to me”) (ATP, 155) (ζ)

There are two things going in this description: first is that the masochist becomes a horse by undergoing the training axiom itself, as the horse does, and so becomes similar; but paramount is this very possibility, that instinctive forces are capable of being replaced with transmitted forces through the mechanism of a program, where the horse is not so much copied, but mapped onto a historic structure. That is, the body of the masochist is given new possibilities (other than its phylogenic and historical forms) through the mapping of new intensities, a transmitting of affects across species bounds. Imitation becomes an actualized line of flight.

It is through this Deleuzian concept, which Elizabeth Grosz calls “[one] of the body as a discontinuous, nontotalizable series of processes, organs, flows, energies, corporeal substances and incorporeal events, speeds and durations…” (164), that the trans-project takes its firmest grip, as trans-. This body becomes a map of intensities structured through a program of becomings as transmitted intensities deterritorialize the body only to reterritorialize it somewhere else through a sharing of affects, and thus possibilities. Might it be constitutive of the trans-identity that there is an informing project of affective and signifying becomings? As clothing, body language, verbalizations, thought processes, role-play, then possibly medicalizations such as rites of hormone intake, social organization of surgeries (appointments, testaments, visits, payments), then the construction of repeatable and perhaps increasingly scrutinized scenes of passing and not-passing become assembled into an entire machine of affect transmission, is not the trans-person the constructor of the body without organs par excellence? But if the trans-person is making a map of themselves, of their body as intensities, what is it they are mapping?

In her book Volatile Bodies, Elizabeth Grosz emphasizes the distinction between surface and depth which Deleuze and Guattari elucidates, one which can be thought of as characterizing the difference between “primitive” and “modern” inscriptions of the body. For Grosz, while the savage inscriptions upon the body, in general, mark relations, modern significations have become markers of interiorities. It is this tension between exterior relations so mapped and the interior wants, desires and aims of a subject’s psychology that seems to play between potential descriptions of trans-identity projects: what they are doing, and what they are wanting. Grosz hopes for us to see our inscribed bodies in a more savage way, as intensive surfaces so that “they create not a map of the body but the body precisely as a map” (139) (η) , in the way that the orchid can be said to map the wasp. The cartographic body of a trans-identity person, through its transmitted forces, becomes a map of relations, if we apply Grosz’ description of the savage:

The body and its privileged zones of sensation, reception, and projection are coded by objects, categories, affiliations, lineages, which engender and make real the subject’s social, sexual, familial, martial, or economic position or identity within a social hierarchy. Unlike messages to be deciphered, they are more like a map of correlating social positions with corporeal intensities (140).

And yet the trans-person, as he or she maps across biological and sociogenic branches through a program of rites of construction and occasions of “passing,” comes to be posited as having an interior by virtue of living these corporeal intensities. Occasions of surface folds and affective transfers between historical and biologically determined kinds become thus spaces for the projections of a modern psychology of depth:

What differentiates savage from civilized systems of inscription is the sign-ladeness of the latter, the creation of bodies as sign systems, texts, narratives, rendered meaningful and integrated into forms capable of being read in terms of personality, psychology, or submerged subjectivity […]

[…]The indefinite and ever-changing impetus and force of bodily sensations can now be attributed to an underlying psyche or consciousness. Corporeal fragmentation, the unity or disunity of the perceptual body, becomes organized in terms of the implied structure of an ego or consciousness, marked by and as a secret and private depth, a unique individual (141)

For Deleuze and Guattari, as they align themselves to such a description of surfaces counter to that signifying what is “interior”, what remains integral for any complete account of desire is that, apart from a psychology of aims and personhood, desire is best seen as rhizomic, especially when representational accounts offer the lure of their greatest explanatory potential. For it is across representational copies, and the moralizing tendency to regard some copies as good and some as mere imitations, that the productive values of desire are to be traced.

An effect of this approach is the way that a trans-experience of desire is to be assessed, both by engaged others, and the persons themselves. Pleasure is the coin with which morality trades most (ι). By Deleuze and Guattari’s telling, it is the collapse of desire into pleasure which constitutes the creation of the subject. “Pleasure is an affection of a person or a subject;” they write, “it is the only way for persons to ‘find themselves’ in the process of desire that exceeds them; pleasures even in the most artificial, are reterritorializations. But the question is precisely whether it is necessary to find oneself” (156). Because the narrative of “finding oneself” makes up a great deal of the subjective experience of many trans-persons, the status of this “self”, in particular the experience of “gender” as it relates to identity must be paid close attention to. If we are to view trans-experiences as so many willful constructions of folds and intensities, mappings of social forms onto the egg of the body, transversally, what are we to make of the very real contestations of selfhood, self-discovery and self-expression well attested to by trans-persons themselves? What is the status of gender, as it is self-conceived and experienced as real, and determinant? And can the rhizomic becomings of Deleuze and Guattari’s description, be re-contextualized into modes of being without becoming entirely hierarchialized into reified strata, strata which condense around a “self”? How does one find out what gender one is?

In some transsexual accounts there is a very real and persistent theme of having to correct one’s body so as to fit the gender one always was. Transsexual Jamison Green, in his book Becoming a Visible Man for instance makes a good example of this when he compares the process of transexuality to “planing the edge of a door so that it fits within its frame” (192). He sees himself as always having been a particular gender, male, and that his body has simply, over the previous parts of his life, mis-communicated to others what he is. Further, he grounds his authority over his gender in terms of an inalienable privacy of experience, invoking the famous “reality” of a tree that falls in the forest:

Gender is a private matter that we share with others; and when we share it, it becomes a social construction […] But to say that without this interaction there is no need for gender is like saying that if a tree fell in the forest and no ear is there to hear the sound, then there was no sound, or perhaps no tree actually fell (191)

There is a significant sense in which this incorrigibility of report serves to authenticate a trans-persons aims, both to others, and to oneself. It is as a person of an incontrovertible gender claim that many of the morally ambiguous acts of self-transformation gain their footing. While not to disparage either the need for such a justification, nor the experience of a surety of knowing one’s gender over time, it is perhaps helpful to examine the foundations of the self-knowing of gender, so as to at the very least gain a perspective of the kinds of terrain trans-persons have to cross—for not all trans-persons may make the claim that they are and have always been a particular gender. In this way we hope to avoid particular entrapping binaries, for instance those between an experiential “soul” and the signifying “body”, so as to inscribe even the most conservative projects of transsexuality—that is, becoming what one already always was—in a landscape of even greater freedom, communication and authority.

I propose that in view of Jamison Green’s notion of private authority, we tentatively treat “gender” in the manner in which Wittgenstein treated all things which we claim to “know only from our own case”. Through Wittgenstein we may provide an account of the solidity of gender, where it is experienced to be solid, and a fluidity where it is experienced to be fluid. And through Wittgenstein, as he takes on representational pictures of the mind wherein we are tempted to think that we directly experience meaning in some unmediated, internal form, we may find bridge to the Analytic tradition in the non-representationalism of Davidson. We may discover that we cannot know directly, in any unmediated way, what “gender” we are, and that to find out what gender we are, we must have “the rest of the mechanism.” (PI §6).

The quickest way to Wittgenstein’s “truth” is perhaps his obiter dictum: “How do I know this colour is red?—It would be an answer to say: ‘I have learnt English’” (PI §381). For what Wittgenstein would like us to see is that when we make judgments about the world (and ultimately about ourselves), it is laterally towards the mutuality of our exchanges that we must turn, if we are looking for the foundation of their truth. There is for Wittgenstein nothing anchoring in the nature of a patch of red paint, for example, that gives us the “how” of our knowing that it is red. Rather, there is a matrix of rules which govern how we talk about things, which allow us to know what is “red”, and what is not. This approach elucidates not only disagreements about “things in the world” but also disagreements over internal presentations and experiences. So, following Wittgenstein, one perhaps can answer, How do I know that I am male? An answer would be: Because I have learned English.

But what if even having learned English seems not to be enough to clear up the meaning of a perception? If way we use the words for specific colors is sunk in the way that we organize ourselves around our experiences of colors, in communication with others, what if our perceptions don’t match up with others? If there was a person who every time saw what supposedly was “red”, and everyone called “red”, instead saw the hypothetical color “ryd” in their Cartesian mind, what would result? One might suggest that the regularity of the use of the word, in concert with the regularity of the experience would work in one of two ways. Either this experience of “ryd” would become synonymous with “red” to the degree that it is for all purposes, it would be “red,” or such a person would come to realize over time that she or he just doesn’t experience “red” the way that other persons do; for instance, “I just don’t find ‘red’ to be a hot color, but it is much more like ‘blue’ or ‘green’ to me”. If gender can be seen as to be like color, the actual experience of being a gender would be one in which the way we use the words “male” and “female” orient us either to their proficiency to describe us, or the divergence of our experience from the norm, and perhaps a bit of both.

There is a well-known picture-game that Wittgenstein offers which helps us to see the place personal experience holds in justifying facts of a matter, his Beetle in a Box. Wittgenstein writes speaking of pain,

Now someone tells me that he knows what pain is only from his own case!—Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a “beetle”. No one can look into anyone else’s box, and everyone says that he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.—Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing.—But suppose the word “beetle” had a use in these people’s language?—If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty.—No, one can ‘divide through’ by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is (PI §293)

The beauty of this example is that it takes relations between people in communication to be fluid and sure. The experience of beetle, becomes established in the regularity of the use of the word “beetle” so much so that the experience itself can be “divided through” in such a perfect, grammatical world. This beetle in the box example was designed for particular claims to know what one is experiencing, only from our own case, what a pain is, what a color is. And despite the idea sometimes forwarded that it is only philosophers who make these kind of “from my own case” claims, it seems entwined in the very nature of personal identity and social authenticity to have a private, unmediated authority of over what one experiences. Here though, Wittgenstein is helping to unseat the idea that we can just look into our own box and know what it is that we see, apart from what all others say and see. In his vision, what is inside the box is not a “something” that can be opened up and shown, or pointed to in any way.

But in order for us to make full use of Wittenstein’s beetle we have to take into account the binary grammar of gender, and thus the particular ways that the language of gender helps organize our experiences of ourselves as gendered. Diverging slightly from his model, let us imagine that not only does the word “beetle” have a use, but so does the word “cricket”. One sensically, in these people’s language, has either one or the other:

Under such a model one can see that through the regularity of the uses of these words “beetle” and “cricket” no matter what really is in the box, one would possibly come to understand that one has one or the other. And there may be cases whereby, even though your anatomy by the norms of designation and use tell you that you should have a beetle inside, it makes the most sense of your experience in the world to say that you had a cricket (just as a person who sees ryd might come to understand that she or he does not see “red” they way that others do, but sees something closer to “blue”). And you might even come to understand that, counter the grammar of such words, sometimes it seems that you have a beetle, and sometimes a cricket, or a strange thing that has a few characteristics of each, and even of something else unnamed. Yet in no case does one know what one has, solely by looking into the box.

We have come from Deleuze’s polyvalent world of affect-becoming, where bodies exist as intensive maps, pure surface values composed of transverse, affective states which allow phyla-genetic paths to cross over, from flower to wasp, from man to horse, and back again, a place where one can become what one historically is not, and we have arrived at a Wittgensteinian world where experience works as what may be described as a kind of center of gravity (κ) , not a “something” but organized by, and potentially organizing a mutuality of meanings, behaviors and concepts, as people come to agree upon the use of words in language-games played. What remains is to join up these two worlds, the Deleuzian one of two-dimensional, coded, affective bodies, and the Wittgensteinian one of horizontal mechanisms of rule-use, under a coherent description such that the powers of both are not diminished, each leading towards a picture of transgender authenticity. I propose the philosophy of Donald Davidson, as a nexus point of such mutuality.

Beginning from Wittgenstein figure of the Beetle in A Box, because we cannot look into anyone else’s box, we must make operative, perhaps hardwired, or even logical assumptions in order to communicate with others and make sense of the world. With such a capacity in mind, Davidson establishes principles charity (λ), guiding non-individuated assumptions about the nature of other persons’ beliefs. Beliefs, he attempts to show, must be of a veridical and coherent nature so as to ground our interpretation of intentional behaviors, and they do so within a necessarily causal picture of the world, a process he calls triangulation.

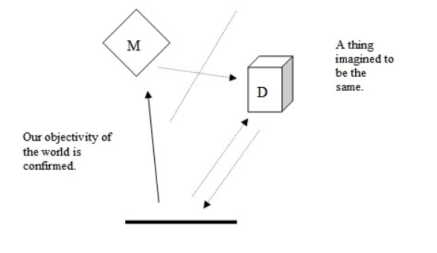

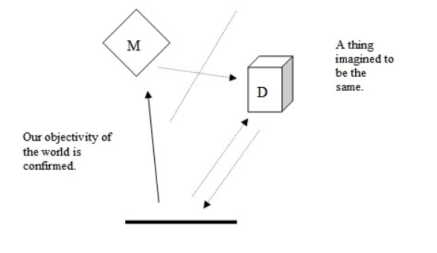

Triangulation exists at the most fundamental level of life: “All creatures” Davidson writes, “classify objects and aspects of the world in the sense that they treat some stimuli as more alike than others. The criterion of such classifying activity is similarity of response” (212); yet this criterion of similarity of response itself can only be derived as a regularity through the regularities of other responses to it; this necessarily creates a nesting of regularities: Thus:

1. There are regularities in the world (M).

2. A creature classifies these regularities.

3. The criterion of this classification is the regularity of this creature’s behavior in response (D).

4. The measure of this criterion is the regularity of behavior of another observing creature (another D, or the perceptive subject), etc.

5. We and others seem to be responding to the same features of the world.

The way that Davidson sees our understanding of others, as language users in a field of meaning, thus is built upon a recognition, and confirmation of regularities; it is these that underwrite our rule-following use of words and that help us form the propositional content of our thoughts; more complexly, it is that as language users we are constantly triangulating between a world and others. It is a world whose events are seen to cause our sensations (μ) , sensations which cause our beliefs (ν) ; and others are those whose mental-states are similarly caused, causing their intentional behaviors (ξ). These behaviors are then interpreted by a normative relation of one to another, via their meanings—that is, we triangulate two positions, our and others so as to gain a world. In this way we are always seeing the world, ourselves and others in an interlocking, mutually dependent relationship, as the world affects others as it also affects us. In such a matrix of relations the world takes on an objective character; all the while we come to have a necessarily intersubjective knowledge of others, and a dependent subjective knowledge of ourselves. These are Davidson’s “three varieties of knowledge” (ο) . To put them in Wittgenstein’s framework: something is “red” in the world because we know that others experience/believe it to be red and because we experience/believe it to be red.

To be more illuminating, I would like to expose these three knowledges to a conceptualization of affective sameness which subsumes Davidson’s principles of charity, filling the gap which lies between “experience” and “belief”. For triangulation necessarily occurs within bodies in relation, bodies of sensation. What I propose is that in interpreting others in the world, we affectively imagine them to be like us, not just at the normative level of beliefs, and thus meaning, but through a governing attribution of sameness. That is, not only do we imagine that like us, others hold a majority of true beliefs about the world, and that these beliefs are reasonably in support of each other, but we also imagine that we would experience the same things as they, under the same conditions.

Thus, if anything allows triangulation to operate all the way down the animal chain of being, it is this affective sharing. It is through this transmitive sharing of sensation, structuring and structured by our beliefs, that new beliefs are able to take hold, and the communication with another attains its bodily relevance. In it simplest form, our experience of the world as real comes about through an affective transmission of sameness.

So while we may very well disagree with others’ interpretations of the world, the beliefs which cause their behaviors, the world and they only make sense if we understand their (mis)interpretations within the larger context of a shared (re)action within a shared world, in an affective communicative capacity (π). We must in some sense “touch” and exchange affects even with those we disagree with, in order to disagree (this is the source of emotional repulsion and moral approbation, judgment involves intimate affective touching, becoming what you object to if only for a moment).

But there is something more involved in our affective and belief-guided imagination of others through which we see the world as it is to be. And this that the affects of others cause us to have affects ourselves. As Spinoza puts this law of affect sharing: “If we imagine a thing like us, toward which we have had no affect, to be affected with some affect, we are thereby affected with a like affect” (EIIIp27). There is, at the foundations of our perceptions of the world a socializing effect, a continuous potential trans-phyla exchange of affects which works to weave bodies together; those of diverse historical genealogies necessarily are put in affective states that others must be imagined to hold, however provisionally, in any attempt to make sense of manifest behaviors. Thus within the index of beliefs about the world is a working bodily exchange of Spinoza’s affectuum imatatio, an imitation of affects, which puts two points of view in concert with the world. Not only do we imagine what others believe, and are therefore able to understand what they mean, but we must feel what we imagine them to feel.

Using this Spinozist conception of affect-sharing we may manage the leap between Davidson’s normative meaning as it spreads out in a pragmatism of sense and interpretation, and Deleuze and Guatttari’s transmitted forces, ethically increasing the number of things a body can do, marrying phyla-genic lines. Davidson grants that a thought may belong to a single person, but not its content, which is mapped, “Even our thoughts about our own mental states occupy the same conceptual space, and are located on the same public map” (218), and this map can be regarded under the affective process of mappings the body . Because Davidson is looking for nonindivuative psychological attitudes (211) which govern our capacity to make sense of the world as language speakers, and sees Wittgenstein’s private language argument as holding not only a community-based “objective check on the correct use of words” but also necessarily a check on “what is the case” (210), the recursivity of pattern recognition in the use of words, as they are used to describe ourselves and the world must be seen as nested and communal relations, building semantic bodies in dependent reflection, not only of belief, but of experience, as it unfolds in the world. It is the case, therefore, that when a biological “woman,” per se, takes on the narrative that “she” has always been a “man”, and too in project willfully constructs the affect experiences of a “man” this transmission of affect must be read as both “real” and “truth telling”, for our accounts of the world are made of nothing more than this. In such a process, not only is the “woman” changed—that body—but so too are “men” changed—those bodies—so as to become however ephemerally a body. It is the force and the coherence of such claims, played out in the constructed struggle to become what one is, that ultimately decides the fact of the matter. In the end the question will be: How well does desire sit in that circulation?

What Davidson’s work does is contextualize the projects of affective becoming which typify the body without organs of Deleuze and Guattari, within an orientation towards a shared world: I am a horse, I am a man, become affect-enriched, world-making procedures, without collapsing them into a purely subjective state of personal psychology, because psychology itself (mental predicates and nonindividuative attitude) is seen as part of a mediating same which constitutes relations . When affects are communicated through program, for instance that of those practiced by the masochist, reinscribing “instinctive forces” with “transmitted forces,” this can be read in context as something more than producing a body without organs, though this descriptions remains; rather, such are dimensionally full productions of affective bodies, as seen to be sharing the world, and cognitively oriented towards it, as it causes internal states in affects spread between perceptions; hence material assemblages become interpretive assemblages of community. For while the masochist may be mapping the intensities of a horse-assemblage upon his body, he is not only doing so, but also in that he is positing himself within the affect-range of a horse he is feeling the world to be causing these distributions, the particularities shared by a horse and himself, as in their union they are determined to hold specific states and potentiated beliefs. Part of cognitive becoming, without a reduction to a Cartesian or even Phenomenological subject, is the transmission of affect across bodies in the experience of a shared and causal world. What Davidson does is compass the expansive ontological work of Deleuze and Guattari’s back towards some of its own origins, that is, back towards an ethical Spinozist description of shared affects in an imaginary binding of the social, in service of the judgment of the world through the creation of affective bodies.

What I propose is that as transgenders and transsexuals come to orient themselves around the meanings and uses of the words for gender, they, like all of us, engage in a radical, body constructive affectuum imatatio. But as Deleuze and Guarttari tell us, this is not taking on the representation of some other thing, but rather taking on the power of an affect as another body might be experiencing itself, as it is undergoing an interaction with the world. It is placing the map of the body in its causal contexts, and thus maintaining the materiality (limits and possibilities) of relations. Trans-individuals are perhaps best seen as engaged in forming an affective ratio in concert with other bodies, such that in a transmission of affect they form together a novel, interpretive perspective of the world.

Spinoza defines a body in a spectacular way:

When a number of bodies…are so constrained by other bodies that they lie upon one another, of if they so move, whether with the same degree of different degrees of speed, that they communicate their motions to each other in a certain fixed manner, we shall say that those bodies are united with one another and that they all together compose one body or Individual (EIIP13def.)

It is this “communicate their motions to each other” which makes of an imitation of affects a material exchange, and also of meaning a praxis experimentation in power, one in which the composite mutuality of experience in response to the world becomes a new locus of experience, across bodies, in so forming a body of communications. In this way, semantic articulations of states of the world, and internal experiences become pathways of bodily constructions of knowledge, in combinatory forms, as the “facts of the matter” continually play out in that praxis of an affective community.

If transgender and transsexual persons can be seen as orienting the cartography of their bodies around the “beetles” or “crickets” that all persons are grammatically supposed to have, with each person coming from the particularities of anatomical and behavioral markers, the histories of what they have been, embedded in the language and expectations of their time, their trans-attempts across those genetic histories mapping upon their bodies the “same” of others imagined to be the same, then trans-acts can be read as multi-individual body-makings, as those of one genealogical history are conjoined with others of others, under the auspice of a single semantic perception. And this new assemblage of perceptions, affects and an operative mutuality of beliefs becomes enriched through the capacities for affect which each genealogical history brings in its cross-pollination of the new assemblage.

In this way, narratives of identity which populate many trans-gender self-descriptions don’t have to be seen merely as collapses of desire into a subjectivity of pleasure, as Deleuze and Guattari may have it. Or to put it another way, the reterritorializations by which Deleuze and Guattari characterize the nature of assemblages that desire forms, don’t have to be read solely in terms of a subject, in the absolute interiority of a “beetle” or a “cricket”. For while it is in terms of identity, gender and self that trans-persons might argue, and even experience their rights as authentic persons, such organized experiences exist through the mutuality of affect as it slides across bodies, keeping parts in communication, through speed, motion and ratio, in a compass-work of an objective world. The experience of such a world need not be dependent upon a subject-state of an “I”. If Davidson has shown us anything, the two are not reciprocal to each other. Rather, it could be read that any localized experience of subject-hood, the pleasures and fears that make up the occasions of passing as another gender for instance, is already part of a communication of affects which make up the body of that semantic sign, as it takes up another organ of perception. And this assemblage of affects, no matter its narrative, should be understood within the specifics of its program and assemblage as they are engaged, that is, the practices, techniques, and material relations, as they produce a shared world through their continual, if only provisional, communications. Just as the subject can be seen as a molarity for Deleuze and Guattari, a passive collapse, the beetle is crossed out by the grammar of Wittgenstein.

Endnotes

α. Such a meeting ground can perhaps very broadly be characterized as “non-representational” thought.

β. As Pearson writes of the ethical dimension of Deleuze and Guattari’s BwO: “The ethical question [knowing what a body can do] concerns the theory and praxis of opening up the body to connections and relations ‘that presuppose an entire assemblage’ made up of ‘circuits, conjunctions, levels and thresholds, passages and distributions of intensity, and territories and deterritorializations” (154). This is viewed as ethical within Spinoza’s determination that any increase in the capacity to affect or be affected is an ethical increase in power and perfection (Spinoza, EIVP38). It is to this Spinozist ground that Deleuze and Guattari must return if they are to make ethical claims for their descriptions.

γ. The terms of deterritorialization and reterritorialization are difficult to define, and can be seen as open and closed states of becoming within the world, respectively. The most helpful analogy is perhaps Deleuze and Guattari’s comparison of a piece of music leaving and returning to a refrain (310-350). Here deterritorialization describes an organism, for instance the orchid, leaving behind its genealogical history, to become what it is not, a wasp, in a flight of transformations, only to become what it is again, when the wasp becomes part of its reproductive system. It is the same for the action of the wasp. Two pieces of music, perhaps, are woven in code, leaving and returning to a refrain.

δ. Man is sick because he is badly constructed./ We must make up our minds to strip him bare in order to scrape off that animalcule that itches him mortally, / god, / and with god / his organs. / For you can tie me up if you wish, / but there is nothing more useless than an organ. /When you will have made him a body without organs, / then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions / and restored him to his true freedom. / Then you will teach him again to dance wrong side out / as in the frenzy of dance halls

and this wrong side out will be his real place.

ε. Deleuze and Guattari describe it this way: “program … At night, put on the bridle and attach my hands more tightly, either to the bit with the chain, or to the big belt right after returning from the bath. Put on the entire harness right away also, the reins and thumbscrews, and attach the thumbscrews to the harness. My penis should be in a metal sheath. Ride the reins for two hours during the day, and in the evening as the master wishes. Confinement for three or four days, hands still tied, the reins alternately tightened and loosened. The master will never approach her horse* without the crop, and without using it. If the animal should display impatience or rebelliousness, the reins will be drawn tighter, the master will grab them and give the beast a good thrashing” (155).

ζ. The quote continues, “Horses are trained: humans impose upon the horse’s instinctive forces transmitted forces that regulate the former, select, dominate, overcode them. The masochist effects an inversion of signs: the horse transmits its transmitted forces to him, so that the masochist’s innate forces will in turn be tamed. There are two series, the horse’s (innate force, force transmitted by the human being), and the masochist’s (force transmitted by the horse, innate force of the human being)”.

η. At more length, on what it means for a body to be a map: “Instead of being read simply as messages, that is, as signifiers of a hidden or inferred signified which is the subject’s interiority, these incisions function to proliferate, intensify, and extend the body’s erotogenic sensitivity. Welts, scars, cuts, tattoos, perforations, incisions, inlays, function quite literally to increase the surface space of the body, creating out of what may have been formless flesh a series of zones, locations, ridges, hollows, contours: places of special significance and libidinal intensity…These incisions and various body markings create an erotogenic surface; they create not a map of the body but the body precisely as a map. They constitute some regions on that surface as more intensified, more significant, than others. In this sense they unevenly distribute libidinal value and forms of social codification across the body” (139).

θ. “My dear Simmias, I suspect that this is not the right way to purchase virtue, by exchanging pleasures for pleasures, and pains for pains, and fear for fear, and greater for less, as if they were coins, but the only right coinage, for which all those things [69b] must be exchanged and by means of and with which all these things are to be bought and sold, is in fact wisdom; and courage and self-restraint and justice and, in short, true virtue exist only with wisdom, whether pleasures and fears and other things of that sort are added or taken away. And virtue which consists in the exchange of such things for each other without wisdom, is but a painted imitation of virtue and is really slavish and has nothing healthy or true in it; but truth is in fact a purification [69c] from all these things, and self-restraint and justice and courage and wisdom itself are a kind of purification”

ι. Dennett makes the use of a similar concept in explaining intentional states in terms of what he calls an “abstract objects” attempts to reconcile Instrumentalism with Realism, “If we go so far as to distinguish them [beliefs] as real (contrasting them with those abstract objects that are bogus), that is because we think they serve as perspicuous representations of real forces, ‘natural properties’ and the like” (29).

κ. Davidson is concerned with the fundamental problems with explaining the value of truth in our attempts to understand others, in particular under a model of communication which he calls “Radical Interpretation.” Under such a view each of us as language speakers are seen to be continually interpreting the speech act of others under working hypotheses of what their intentions, beliefs and desires are, and their causal relations to the world. When making sense of others we regularly employ what he calls the principle of coherence, which allows us to “discover a degree in logical consistency in the thought of the speaker,” and the principle of correspondence that gives us to “take the speaker to be responding to the same features of the world that he (the interpreter) would be responding to under similar circumstances” (211). These two principles are examples of what has been called principles of charity, and he contends that without such charity we cannot come even understand what it is that another person is saying, to even come to the point of disagreeing with it.

μ. “The relation between a sensation and a belief cannot be logical, since sensations are not beliefs or other propositional attitudes. What then is the relation? The answer is, I think, obvious: the relations is causal” (“A Coherence Theory of Truth” 229).

ν. Beliefs include a class of mental predicates, which include desires, fears and wants.

ξ. “An action, for example, must be intentional under some description, but an action is intentional only if it is caused by mental factors, such as beliefs and desires” (“Three Varieties of Knowledge” 216).

ο. “Until a baseline has been established by communication with someone else, there is no point in saying one’s own thoughts or words have a propositional content. If this is so, then it is clear that knowledge of another mind is essential to all thought and all knowledge. Knowledge of another mind is possible, however, only if one has knowledge of the world, for the triangulation which is essential to thought requires that those in communication recognize that they occupy positions in a shared world” (213).

π. And indeed, when others act in ways that seem incommensurate with “reality,” it is upon the nature of their beliefs that we place our attention, understanding those beliefs to somehow be erroneously caused by the world, and thus explanatory of something of their natures, that is, traceable to a genealogy of thought and experiences which strikes us as incommensurate with our own, an incommensurability founded upon either an error or an essentialized kind. In such a way, even those with whom we vehemently disagree can still report on the world so that the world retains its objective character, as it is confirmed by the (mis)perceptions of others (filtered through their beliefs or experiences which we take in account). But only by imagining others to hold beliefs and affective states that we too might be able to hold do even our greatest disagreements still hold relevance.

Works Cited

Ayasse, Manfred, et al. (2003). Pollinator attraction in a sexually deceptive orchid by means of unconventional chemicals. The Royal Society. 24 January, 2003. pp 517-522.

Davidson Donald. “A Coherence Theory of Truth”. The Essential Davidson. New York: Oxford University Press. 2006.

–.“Three Varieties of Knowledge”. Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Guattari, Félix. a thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Trans. Brian

Massumi. Minneapolis: Minnesota Press, 1987.

Dennett, Daniel C. (Jan., 1991). “Real Patterns”. The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 88, No. 1. pp. 27-51.

Green, Jamison. Becoming a Visible Man. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2004.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Pearson, K. A.. Germinal Life: The difference and repetition of Deleuze. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Spinoza, Baruch. The Collected Works of Spinoza, volume 1. Trans. Edwin Curley. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Trans. Elizabeth Anscombe. 3rd Edition, Hardback. Cornwall: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2004.

Wong, B. B. and Schiestl, F. P.. How an orchid harms its pollinator. The Royal Society. 3 July, 2002. pp 1529-1532.

Recent Comments